Key Findings

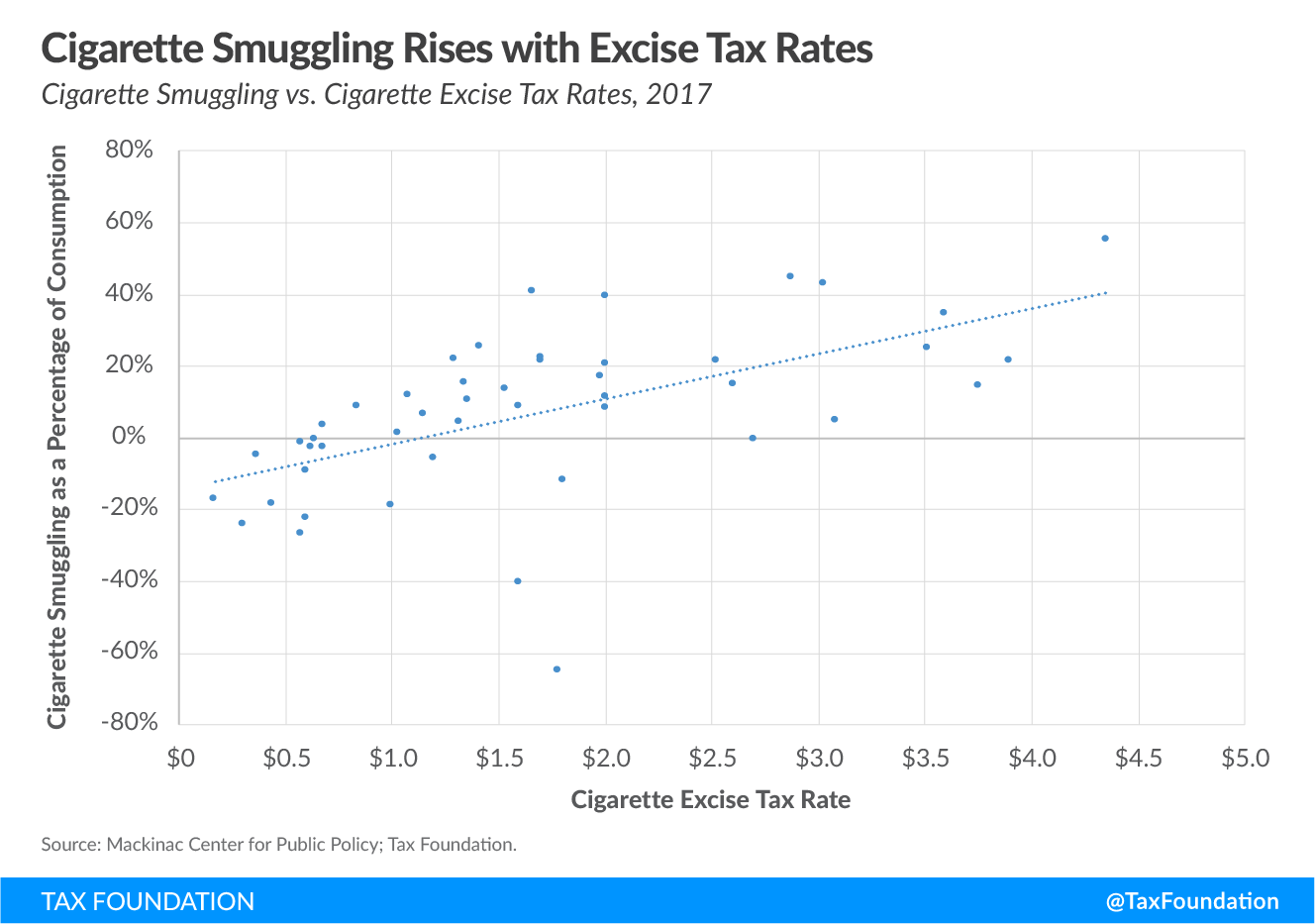

- Excessive tax rates on cigarettes approach de facto prohibition in some states, inducing black and gray market movement of tobacco products into high-tax states from low-tax states or foreign sources.

- New York has the highest inbound smuggling activity, with an estimated 55.4 percent of cigarettes consumed in the state deriving from smuggled sources in 2017. New York is followed by California (44.6 percent of consumption smuggled), Washington (42.8 percent), New Mexico (40.8 percent), and Minnesota (34.6 percent).

- New Hampshire has the highest level of outbound smuggling at 65 percent of consumption, likely due to its relatively low tax rates and proximity to high-tax states in the northeastern United States. Following New Hampshire is Delaware (40.6 percent outbound smuggling), Idaho (26.8 percent), Virginia (24.2 percent), and Wyoming (22.4 percent).

- Pennsylvania, following a cigarette tax increase from $1.60 to $2.60 in early 2016, has seen a significant increase in smuggling into the state.

- Cigarette tax rates increased in 37 states and the District of Columbia between 2006 and 2017.

- Lawmakers interested in taxing and regulating electronic cigarettes should understand the policy trade-offs related to high taxation or bans of nicotine products. With distribution networks already well-developed, criminal gangs are poised to expand into vapor products.

Tobacco Tax Differentials across States Cause Significant Smuggling

The crafting of tax policy can never be divorced from an understanding of the law of unintended consequences, but it is too often disregarded or misunderstood in political debate, and sometimes policies, however well-intentioned, have unintended consequences that outweigh their benefits.

One notable consequence of high state cigarette excise tax rates has been increased smuggling as people procure discounted packs from low-tax states and sell them in high-tax states. Growing cigarette tax differentials have made cigarette smuggling both a national problem and, in some cases, a lucrative criminal enterprise.

Each year, scholars at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a Michigan think tank, use a statistical analysis of available data to estimate smuggling rates for each state.[1] Their most recent report uses 2017 data and finds that smuggling rates generally rise in states after they adopt cigarette tax increases. Smuggling rates have dropped in some states, often where neighboring states have higher cigarette tax rates. Table 1 shows the data for each state, comparing 2017 and 2006 smuggling rates and tax changes.

New York is the highest net importer of smuggled cigarettes, totaling 55.4 percent of total cigarette consumption in the state. New York also has one of the highest state cigarette taxes ($4.35 per pack), not counting the additional local New York City cigarette tax ($1.50 per pack). Smuggling in New York has risen sharply since 2006 (+55 percent), as has the tax rate (+190 percent). In October, three people were charged in connection with smuggling cigarettes on the Staten Island Ferry. They were in possession of 30,000 untaxed cigarettes and $63,000 in cash.[2]

Smuggling in Pennsylvania has increased sharply since the last data release. The state increased the cigarette excise tax from $1.60 to $2.60 and as a result switched from having net outbound smuggling to net inbound smuggling. In 2015, Pennsylvania had outbound smuggling of 2.0 percent, but following the increase, the state inbound smuggling is at 14.7 percent. Over the same period, outbound smuggling increased in nearby low-tax Delaware, from 20.3 percent to 40.6 percent, suggesting that many cartons of cigarettes are crossing the border from one state to the other.

Other peer-reviewed studies provide support for these findings.[3] A 2018 study in Public Finance Review examined littered packs of cigarettes across 132 communities in 38 states, finding that 21 percent of packs did not have proper local stamps.[4]

As noted by LaFaive and Nesbit, authors of the Mackinac Center study, smuggling comes in different forms: “casual” smuggling, where smaller quantities of cigarettes are purchased in one area and then transported for personal consumption, and “commercial” smuggling, which is large-scale criminal activity that can involve counterfeit state tax stamps, counterfeit versions of legitimate brands, hijacked trucks, or officials turning a blind eye.[5]

The Mackinac Center has cited numerous examples over the many editions of this report, including stories of a Maryland police officer running illicit cigarettes while on duty, a Virginia man hiring a contract killer over a cigarette smuggling dispute, and prison guards caught smuggling cigarettes into prisons.

Policy responses in recent years have included banning common carrier delivery of cigarettes,[6] greater law enforcement activity on interstate roads,[7] differential tax rates near low-tax jurisdictions,[8] and cracking down on tribal reservations that sell tax-free cigarettes.[9] However, the underlying problem remains: high cigarette taxes amount to a “price prohibition” of the product in many U.S. states.[10]

International Smuggling and Counterfeiting Puts Consumers at Risk

While buying cigarettes in low-tax states and selling in high-tax states is widespread in the United States, other methods for evading federal, state, and local taxes are popular. One way that criminals grow their profits is by avoiding the legal market completely. They produce counterfeit cigarettes with the look and feel of legitimate brands and sell them with counterfeit tax stamps. Many of these products are smuggled from China, with one source estimating that Chinese counterfeiters produce 400 billion cigarettes per year to meet international demand.[11]

Global focus on counterfeit cigarettes has forced the criminals to innovate. A growing global problem is the so-called illicit whites or cheap whites. These products are produced legally in low-tax jurisdictions, but often intended for smuggling.[12]

These smuggled and counterfeit cigarettes are dangerous products as they do not live up to the quality control standards imposed on legitimate brand cigarettes. Pappas et al. (2007) find that counterfeit cigarettes can have as much as seven times the lead of authentic brands, and close to three times as much thallium, a toxic heavy metal.[13] Other sources report finding insect eggs, dead flies, mold, and human feces in counterfeit cigarettes.[14]

During prohibition of alcohol in the United States during the 1920s, increased enforcement did not manage to significantly decrease the prevalence of bootlegging because the profit margins were so large, and the distribution networks sophisticated. The same is true for today’s cigarette smugglers.

In June 2019, Canadian authorities arrested nine people who reportedly smuggled over one million pounds of tobacco (valued at CA $110 million). According to police the group was involved in both theft and arms trafficking.[15] Also this year, in Europe, authorities arrested 22 people across five countries. The organized crime organization is suspected of large-scale cigarette trafficking, assassinations, and money laundering, netting an estimated $750 million over the past two years.[16]

Global illicit trade in tobacco is a growing problem, but is considered low-risk, high-reward. Billions of dollars are made each year, and the trade involves corruption, money laundering, and terrorism.[17] According to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF): “Large-scale organized smuggling likely accounts for the vast majority of cigarettes smuggled globally.”[18] These operations hurt governments, who lose out on revenue; consumers, because the products often don’t adhere to health standards; legal businesses, which cannot compete with illicit products; and the general respect of the law.

A Cautionary Tale

Most vapor product users also smoked cigarettes.[19] With this in mind, we can imagine the behaviors of vapers to mirror those of smokers. Throughout the fall of 2019, both federal and state lawmakers have called for flavor bans and cigarette-level taxation of vapor products. As the data from cigarettes clearly show, the risk of creating a new black market or fueling an existing one with operators willing and able to supply nicotine products to consumers is significant.

There are already reports of nicotine-containing liquid coming into the U.S. from questionable sources.[20] In addition to tax evasion—costing states billions in lost tax revenue—black market e-liquid and cigarettes can be extremely unsafe.[21] The latest stories about serious pulmonary diseases have prompted the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to publish a warning about black market THC-containing liquid (the psychoactive compound in marijuana).[22] Reports of illicit products containing dangerous chemicals resulting in serious medical conditions have been released over the last months.[23] Providing vapers with a well-regulated legal market will limit the distribution of illegal products.

On top of the dangers to consumers, the legal market would also suffer, as untaxed and unregulated products would have significant competitive advantages over high-priced legal products. This would impact not only the large number of small business owners operating over 10,000 vape shops around the country, but also convenience stores and gas stations relying heavily on vapers as well as tobacco sales. Policymakers should not lose sight of the law of unintended consequences as they set rates and regulatory regimes for tobacco and vapor products alike.

| Source: Mackinac Center for Public Policy; Tax Foundation |

| State | 2017 Tax | 2017 Consumption Smuggled (positive is inflow, negative is outflow) | 2006 Consumption Smuggled (positive is inflow, negative is outflow) | 2017 Rank | Rank Change since 2016 | Excise Tax Rate change 2006-2017 |

| AL | $ 0.675 | -2.50% | 0.50% | 34 | 1 | 59% |

| AK | $2.00 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 25% |

| AR | $1.15 | 6.29% | 3.9 | 26 | 2 | no change |

| AZ | $2.00 | 39.29% | 32.10% | 5 | -3 | 69% |

| CA | $2.87 | 44.55% | 34.60% | 2 | 5 | 230% |

| CO | $0.84 | 8.82% | 16.60% | 23 | 1 | no change |

| CT | $3.90 | 21.40% | 12.30% | 11 | 4 | 158% |

| DE | $1.60 | -40.55% | -61.50% | 46 | -2 | 191% |

| FL | $ 1.339 | 15.16% | 6.90% | 16 | 3 | 294% |

| GA | $0.37 | -4.80% | -0.30% | 36 | 1 | no change |

| IA | $1.36 | 10.57% | 2.40% | 22 | 0 | 278% |

| ID | $0.57 | -26.77% | -6.00% | 45 | 1 | no change |

| IL | $1.98 | 17.20% | 13.70% | 15 | 1 | 102% |

| IN | $ 0.995 | -18.81% | -10.80% | 42 | -1 | 79% |

| KS | $1.29 | 21.81% | 18.40% | 10 | 4 | 63% |

| KY | $0.60 | -9.25% | -6.40% | 38 | 0 | 100% |

| LA | $1.08 | 11.77% | 6.40% | 20 | 1 | 200% |

| MA | $3.51 | 24.99% | 17.50% | 8 | 0 | 132% |

| MD | $2.00 | 11.35% | 10.40% | 21 | -3 | 100% |

| ME | $2.00 | 8.28% | 16.60% | 25 | 0 | no change |

| MI | $2.00 | 20.55% | 31.00% | 14 | -1 | no change |

| MN | $3.59 | 34.62% | 23.60% | 6 | -1 | 149% |

| MO | $0.17 | -17.10% | -11.30% | 40 | 0 | no change |

| MS | $0.68 | 3.32% | -1.70% | 29 | 1 | 36% |

| MT | $1.70 | 21.34% | 31.20% | 12 | 0 | no change |

| NC | $0.45 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 50% |

| ND | $0.44 | -18.66% | 3.00% | 41 | -2 | no change |

| NE | $0.64 | -0.67% | 12.00% | 32 | 0 | no change |

| NH | $1.78 | -65.04% | -29.70% | 47 | 0 | 123% |

| NJ | $2.70 | -0.50% | 38.40% | 31 | -5 | 13% |

| NM | $1.66 | 40.76% | 39.90% | 4 | 0 | 82% |

| NV | $1.80 | -11.85% | 4.80% | 39 | -33 | 125% |

| NY | $4.35 | 55.35% | 35.80% | 1 | 0 | 190% |

| OH | $1.60 | 8.49% | 13.10% | 24 | -1 | 28% |

| OK | $1.03 | 1.03% | 9.60% | 30 | 1 | no change |

| OR | $1.32 | 4.19% | 21.10% | 28 | -1 | 12% |

| PA | $2.60 | 14.73% | 12.90% | 17 | 17 | 93% |

| RI | $3.75 | 14.37% | 43.20% | 18 | -1 | 52% |

| SC | $0.57 | -1.40% | -8.10% | 33 | 0 | 14% |

| SD | $1.53 | 13.52% | 5.30% | 19 | 1 | 189% |

| TN | $0.62 | -2.78% | -4.50% | 35 | 1 | 210% |

| TX | $1.41 | 25.18% | 14.80% | 7 | 2 | 244% |

| UT | $1.70 | 22.13% | 12.90% | 9 | 2 | 145% |

| VA | $0.30 | -24.21% | -23.50% | 44 | -2 | no change |

| VT | $3.08 | 4.77% | 4.50% | 27 | 2 | 72% |

| WA | $ 3.025 | 42.79% | 38.20% | 3 | 0 | 49% |

| WI | $2.52 | 21.20% | 13.10% | 13 | -3 | 227% |

| WV | $1.20 | -5.81% | -8.40% | 37 | 6 | 118% |

| WY | $0.60 | -22.36% | -0.60% | 43 | 2 | no change |

Figure 1

Figure 2

[1] See Michael LaFaive, Todd Nesbit, and Michael Lucci, “Smuggled Smokes: California Closes in on New York,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, May 20, 2019, https://www.mackinac.org/archives/2019/Smuggled_Smokes_CA_NY.pdf; Michael D. LaFaive, Todd Nesbit, and Scott Drenkard, “Cigarette Taxes and Smuggling: A 2016 Update,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Dec. 19, 2016, https://www.mackinac.org/s2016-09; Michael D. LaFaive, Todd Nesbit, and Scott Drenkard, “Cigarette Smugglers Still Love New York and Michigan, but Illinois Closing In,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Jan. 14, 2015, http://www.mackinac.org/20900; Michael D. LaFaive and Todd Nesbit, “Cigarette Smuggling Still Rampant in Michigan, Nation,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Feb. 17, 2014, http://www.mackinac.org/19725; Michael D. LaFaive and Todd Nesbit, “Higher Cigarette Taxes Create Lucrative, Dangerous Black Market,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Jan. 8, 2013, http://www.mackinac.org/18128; Michael D. LaFaive and Todd Nesbit, “Cigarette Taxes and Smuggling 2010: An Update of Earlier Research,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Dec. 17, 2010, http://www.mackinac.org/14210; Michael D. LaFaive, Patrick Fleenor, and Todd Nesbit, “Cigarette Taxes and Smuggling: A Statistical Analysis and Historical Review,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Dec. 2, 2008, http://www.mackinac.org/10005.

[2] Irene Spezzamonte, “800 cartons of illicit cigarettes, $63,500 in cash seized on Staten Island, feds say,” silive.com, Oct. 18, 2019, https://www.silive.com/crime/2019/10/feds-seize-800-cartons-of-illicit-cigarettes-63500-in-cash-on-staten-island.html.

[3] Cf Michael F. Lovenheim, “How Far to the Border?: The Extent and Impact of Cross-Border Casual Cigarette Smuggling,” National Tax Journal 61:1 (March 2008), https://www.ntanet.org/NTJ/61/1/ntj-v61n01p7-33-how-far-border-extent.pdf?v=%CE%B1&r=04833355782549953; R. Morris Coats, “A Note on Estimating Cross-Border Effects of State Cigarette Taxes,” National Tax Journal 48:4 (December 1995), 573-84, https://www.ntanet.org/NTJ/48/4/ntj-v48n04p573-84-note-estimating-cross-border.pdf?v=%CE%B1&r=35923133871196367; Mark Stehr, “Cigarette tax avoidance and evasion,” Journal of Health Economics 24:2 (March 2005), 277-97, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167629604001225.

[4] Shu Wang, David Merriman, and Frank Chaloupka, “Relative Tax Rates, Proximity, and Cigarette Tax Noncompliance: Evidence from a National Sample of Littered Cigarette Packs,” Public Finance Review 47:2 (March 2019), 276-311.

[5] Scott Drenkard, “Tobacco Taxation and Unintended Consequences: U.S. Senate Hearing on Tobacco Taxes Owed, Avoided, and Evaded,” Tax Foundation, July 29, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/tobacco-taxation-and-unintended-consequences-us-senate-hearing-tobacco-taxes-owed-avoided-and-evaded/.

[6] Curtis S. Dubay, “UPS Decision Unlikely to Stop Cigarette Smuggling,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 25, 2005, https://taxfoundation.org/ups-decision-unlikely-stop-cigarette-smuggling/.

[7] See Gary Fields, “States Go to War on Cigarette Smuggling,” The Wall Street Journal, July 20, 2009, http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB124804682785163691.

[8] Mark Robyn, “Border Zone Cigarette Taxation: Arkansas’s Novel Solution to the Border Shopping Problem,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 9, 2009, http://taxfoundation.org/article/border-zone-cigarette-taxation-arkansass-novel-solution-border-shopping-problem.

[9] See Joseph Bishop-Henchman, “New York Governor Signs Law to Tax Cigarettes Sold on Tribal Lands,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 16, 2008, http://taxfoundation.org/blog/new-york-governor-signs-law-tax-cigarettes-sold-tribal-lands.

[10] See Patrick Fleenor, “Tax Differentials on the Interstate Smuggling and Cross-Border Sales of Cigarettes in the United States,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 1, 1996, http://taxfoundation.org/article/tax-differentials-interstate-smuggling-and-cross-border-sales-cigarettes-united-states.

[11] Te-Ping Chen, “China’s Marlboro Country, Center for Public Integrity, June 29, 2009, https://reportingproject.net/underground/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=9:chinas-marlboro-country&catid=3:stories&Itemid=22.

[12] Roger Bate, Cody Kallen, and Aparna Mathur, “The perverse effect of sin taxes: the rise of illicit white cigarettes,” Applied Economics, Aug. 5, 2019, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00036846.2019.1646403?journalCode=raec20.

[13] R.S. Pappas et al., “Cadmium, Lead, and Thallium in Smoke Particulate from Counterfeit Cigarettes Compared to Authentic US Brands,” Food and Chemical Toxicology 45:2 (Aug. 30, 2006), 202-209.

[14] International Chamber of Commerce, Commercial Crime Services, “Counterfeit Cigarettes Contain Disturbing Toxic Substances,” https://icc-ccs.org/index.php/360-counterfeit-cigarettes-contain-disturbing-toxic-substances.

[15] CTV News, “Nine arrested in major contraband tobacco bust,” June 26, 2019, https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/nine-arrested-in-major-contraband-tobacco-bust-1.4483651.

[16] The Guardian, “More than 20 arrested across Europe in swoop on drug gang,” May 22, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/may/22/22-arrested-across-europe-in-swoop-on-alleged-dangerous-drug-gang.

[17] DOS, DOJ, DOT, DOHS, DOHHS, “The Global Illicit Trade In Tobacco: A Threat To National Security,” December 2015, https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/250513.pdf.

[18] The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), “FATF Report: Illicit Tobacco Trade,” June 2012, 9, https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Illicit%20Tobacco%20Trade.pdf.

[19] Truth Initiative, “E-cigarettes: Facts, stats and regulations,” July 19, 2018, https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/e-cigarettes-facts-stats-and-regulations.

[20]Julie Bosman and Matt Richtel, “Vaping Bad: Were 2 Wisconsin Brothers the Walter Whites of THC Oils?” The New York Times, Sept. 17, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/15/health/vaping-thc-wisconsin.html.

[21] National Research Council, Understanding the U.S. Illicit Tobacco Market: Characteristics, Policy Context, and Lessons from International Experiences (Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press), 2015, 4.

[22] U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “Vaping Illness Update: FDA Warns Public to Stop Using Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-Containing Vaping Products and Any Vaping Products Obtained Off the Street,” Oct. 4, 2019, https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/vaping-illnesses-consumers-can-help-protect-themselves-avoiding-tetrahydrocannabinol-thc-containing.

[23] See David Downs, Dave Howard, and Bruce Barcott, “Journey of a tainted vape cartridge: from China’s labs to your lungs,” Leafly, Sept. 24, 2019, https://www.leafly.com/news/politics/vape-pen-injury-supply-chain-investigation-leafly; and Conor Ferguson, Cynthia McFadden, Shanshan Dong, and Rich Schapiro, “Tests show bootleg marijuana vapes tainted with hydrogen cyanide,” NBC News, Sept. 27, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/health/vaping/tests-show-bootleg-marijuana-vapes-tainted-hydrogen-cyanide-n1059356.