The wealth tax has been pushed to the forefront of tax policy debates to combat wealth inequality. Presidential candidates Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) both released proposals to tax the rich as part of their 2020 platforms. Senator Warren’s tax plan features a wealth tax rate of 2 percent each year on wealth over $50 million and 6 percent on wealth over $1 billion as part of her Medicare for All plan. Senator Sanders proposed a more progressive wealth tax of up to 8 percent on net wealth over $10 billion.

Wealth taxes are not well-known to taxpayers in the United States. In the current tax system, property taxes and the estate tax are special cases of wealth tax, although property taxes are commonly used at the state level. Annual comprehensive wealth taxes have never been implemented in the United States. Individual income taxes have been a main source of U.S. federal revenue for decades.

It is easier for us to understand the basics of a wealth tax when we compare it to the individual income tax.

Tax Base

Wealth taxes are imposed on individual’s net wealth, or the market value of their total owned assets minus liabilities. Wealth taxes can be narrowly or widely defined, and depending on the definition of wealth, the base for a wealth tax can vary. For example, Senator Warren proposed a broad-based wealth tax plan, applying to both domestic and foreign assets of U.S. citizens.

Economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, who have consulted with presidential candidates on their tax plans, define net wealth as financial and nonfinancial assets net debts, including bonds and mutual funds, pensions, housing, public equity, and private business assets, but excluding human capital, durable goods, nonprofits, and unfunded defined benefit pension plans.

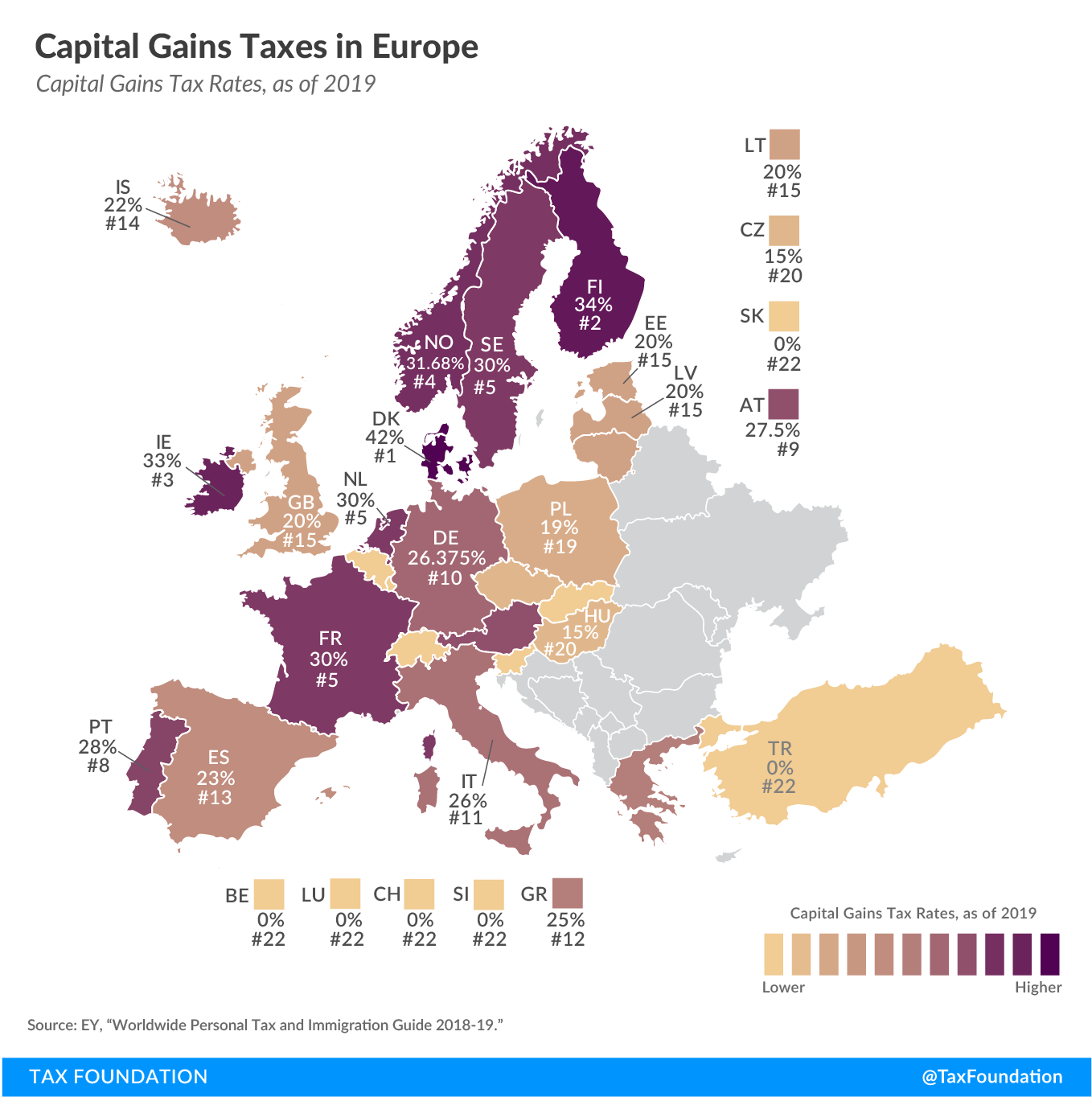

Countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) with a net wealth tax adopt different wealth tax bases. For example, France, Spain, and Sweden exempt business assets from their wealth tax due to the concern of discouraging productive investments.

The U.S. federal income tax system is based on the Haig-Simmons income definition. The income tax base is defined as current consumption and the increase in one’s net worth during that year (with some exceptions like IRAs). Labor and capital income are the two major components of the income tax base. Labor income includes salaries, wages, and fringe benefits; capital income includes dividends, interest, and capital gains income.

More simply, wealth taxes are levied on the wealth stock, or the total amount of net wealth a taxpayer owns, while an income tax is imposed on the flow from the wealth stock. The income earned from returns to wealth becomes part of the wealth tax base for the next year, as the wealth stock grows.

Differences in Taxing Capital Income

The current income tax system on capital gains is levied when a gain is realized, meaning capital gains taxes are only collected when assets are sold and there is a gain between the time they are purchased and sold. Unrealized capital gains are not taxed, as the tax is deferred until they are realized. Wealthy people tend to defer realizing capital gains; the top 1 percent holds about half of the unrealized capital gains. This is one reason some argue that the wealthy do not pay enough in tax.

A wealth tax would theoretically reduce deferral and lock-in incentives, since wealth would be taxed on an accrual basis rather than realization basis. The accrual basis means that accrued gains and principal assets are taxed on a yearly basis instead of when the gains and assets are sold or realized. If the market value of assets and liabilities are properly and regularly valued, the wealth tax will be levied on the market value of capital assets on a yearly basis. However, the small number of countries with wealth tax experience shows that the wealth tax is not an efficient way to raise revenue due to the administrative difficulties and disappointing levels of revenue collection.

Understanding the Size of Wealth Tax Rates

A wealth tax levied at a low rate may hide the real size of the effect on after-tax return. Consider a taxpayer who owns corporate bonds with a fixed return of 5 percent each year. The asset is valued at $50 million at the beginning of the year. Starting from Year 1, the return from this asset will be counted as asset appreciation and taxed as capital income at the end of the year. In this case, a levy of a 1 percent wealth tax is equivalent to a 20 percent income tax; both would leave the taxpayer and government in the same place for taxes paid and revenue collected, as shown in the table below. In this example, we assume there is no overlap between these taxes. If the wealth tax were enacted at 5 percent, it would be equal to a 100 percent income tax, which is a zero after-tax return.

| Source: Author’s calculations. | ||

| Wealth Tax | Income Tax | |

|---|---|---|

| Net Assets ($millions) | 50 | 50 |

| Rate of Return | 5% | 5% |

| Tax Rate | 1% | 20% |

| Revenue | 0.5 | 0.5 |

Interactions between Income Taxes and A Wealth Tax

If established, a wealth tax would become a new, separate tax system in addition to the income tax. The interaction between wealth taxes and income taxes is worth thinking through.

An increase in the income tax rate will reduce the wealth tax base, which is calculated as subtracting income tax liability from current assets if we assume income tax is imposed before the wealth tax.

On the other hand, a wealth tax will reduce the stock of income-generating assets if no return to these assets comes in. When the return to capital is considered, net wealth assets may still grow if the return to wealth is larger than the wealth tax levy. If the wealth tax levy is greater than the return to wealth, the wealth stock declines, resulting in lower income generation.

In the table below, Scenarios A and B display how wealth levels and the after-tax return will change under a 1 percent wealth tax and a 6 percent wealth tax. Under Scenario B, the after-tax return becomes negative, as the 6 percent wealth tax exceeds the before-tax rate of return of 5 percent. This reduces wealth accumulation and may lower the amount of assets businesses might have available and erode the wealth tax base.

| Scenario A | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wealth Tax Rate | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| Assets ($millions), beginning of year | 50 | 51.48 | 53.00 |

| Before-tax Return | 5% | 5% | 5% |

| Income Tax Base | 2.50 | 2.57 | 2.65 |

| Capital Income Tax (20%) | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.53 |

| Wealth Tax Base ($millions) | 52.00 | 53.54 | 55.12 |

| Wealth Tax | 0.52 | 0.54 | 0.55 |

| After-tax return | 3.0% | 3.0% | 3.0% |

| Scenario B | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 |

| Wealth Tax Rate | 6% | 6% | 6% |

| Assets ($millions), beginning of year | 50 | 48.88 | 47.79 |

| Before-tax Return | 5% | 5% | 5% |

| Income Tax Base | 2.50 | 2.44 | 2.39 |

| Capital Income Tax (20%) | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| Wealth Tax Base ($millions) | 52.00 | 50.84 | 49.70 |

| Wealth Tax | 3.12 | 3.05 | 2.98 |

| After-tax return | -2.2% | -2.2% | -2.2% |

| Source: Author’s calculations. | |||

Conclusion

An annual comprehensive wealth tax has never been adopted in the U.S. If enacted, it will be a separate tax structure from the current federal tax system. Wealth taxes are levied on the wealth stock on an accrual basis, while income taxes are levied on the flow from the wealth stock. A low wealth tax rate is equivalent to a high-rate income tax. The interaction between wealth taxes and the existing income taxes must be considered when analyzing a wealth tax plan.